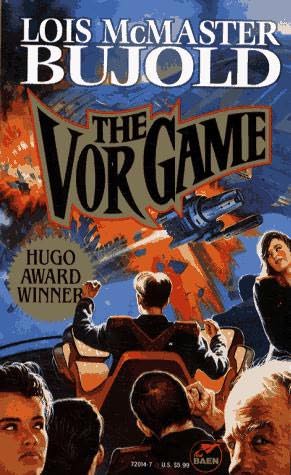

The Vor Game was Bujold’s first Hugo-winning novel, and it’s here that the series really hits its stride, and also where it (briefly) starts to look like a normal series. Chronologically, The Vor Game follows on from The Warrior’s Apprentice, with the novella The Mountains of Mourning (which also won a Hugo) coming between them. And Young Miles gives you just that, and I think that every single time I’ve read this series (certainly every time I’ve re-read it) I’ve read them in just that order. I had never actually consciously realised that Bujold had written Brothers in Arms first and come back to fill in this piece of the continuity.

I think The Vor Game would probably be a perfectly reasonable place to pick up the series, and as this is the first published novel where the writing quality is really high, it might even be a good place. It has an entirely self-contained and very exciting plot. And it’s largely about what it means to be Vor, and Miles’s subordination problems.

At the end of The Warrior’s Apprentice, Miles’s reward is entry into the Imperial Academy. In The Vor Game he has just graduated from it and been given an assignment—weatherman on an infantry base on Kyril Island. He’s told if he can keep his nose clean he’ll get ship assignment in six months, and of course he doesn’t keep his nose clean. He is sent on a secret mission to the Hegen Hub for ImpSec. He’s along to deal with the Dendarii, his superiors are supposed to find out what’s going on. He finds out what’s going on, and goes on to rescue the Emperor and defeat the Cetagandans.

As a plot summary this does read just like more of The Warrior’s Apprentice and kind of what you’d expect in another volume—Barrayar and duty against the mercenaries and fun. And there’s a lot about this story that is pure bouncing fun. He does retake the mercenaries wearing slippers. (He’s so like his mother!) At one point Miles has his three supposed superiors, Oser, Metzov, and Ungari all locked up in a row, and Elena remarks that he’s hard on his superiors.

In The Warrior’s Apprentice, it’s MilSF fun with unexpected depths. Here the depths are fully integrated and entirely what the book’s about. Practically all the characters are as well-rounded as the best of them are in the earlier books. We see a little bit of Ivan, a lot of Gregor, a little of Aral, of Elena, Bel, and there are the villains, Cavilo and Metzov, complicated people, and interesting distorting mirrors of Miles.

And Miles here is the most interesting of all. For the first time we see Miles longing to be Naismith almost as an addiction—Naismith is his escape valve. In Brothers in Arms there’s the metaphor of Miles as an onion, Admiral Naismith being encompassed by Engisn Vorkosigan who is encompassed by Lord Vorkosigan who is encompassed by Miles. Here we see that working. It isn’t just his subordination problem, the way he sees his superiors as future subordinates. (All my family are teachers, and I had the exact same problem in school of failing to be awed by the people assigned to teach me.) The most interesting thing about Miles is the tension between Betan and Barrayaran, between his personalities. He says to Simon at the end that he couldn’t keep on playing ensign when the man who was needed was Lord Vorkosigan, and thinks, or Admiral Naismith. He genuinely feels that he knows best in all situations and he can finesse it all—and so far, the text is entirely on his side. Miles does know best, is always right, or at worst what he does is “a” right thing to do, as Aral says about the freezing incident.

The book is called “The Vor Game” because one of the themes is about what it means to be Vor and bound by duty. I disagree with people who think “The Weatherman” should be in Borders of Infinity and not here. Even if it wasn’t absolutely necessary because it introduces Metzov and dictates what comes after, it would be necessary to introduce that Vor theme—Miles can make threatening to freeze stick not because he’s an officer but because he’s Vor, and because he’s Vor he has to do it.

Feaudalism is an interesting system, and one not much understood by people these days. Bujold, despite being American and thus from a country that never had a feudal period, seems to understand it deeply and all through. Vor are a privileged caste on Barrayar, a warrior caste, but this gives them duties as well as privileges. Miles standing freezing with the techs who refuse to endanger their lives, unnecessarily cleaning up the fetaine spill, is a man under obligation. Similarly, Gregor, who has tried to walk away from it all, accepts his obligations at the end. Gregor, with supreme power, is the most bound of all. (And he wishes that Cavilo had been real.) He isn’t a volunteer, and yet by the end of the book he has volunteered. It’s a game, an illusion, and yet it’s deadly serious. In The Warrior’s Apprentice, Miles uses it to swear liegemen left and right, here we see how it binds him. And that of course feeds back to The Mountains of Mourning, which shows us why it is actually important, at the level it actually is.

The Vor Game looks like a sensible safe series-like sequel to The Warrior’s Apprentice, it’s another military adventure, it’s another conflicted Barrayaran plot, and Miles saves the day again. It’s the first book in the series that does look like that—and pretty much the last one too. What Bujold is setting up here is Mirror Dance. To make that book work, she had to have not only Mark from Brothers in Arms she had to have all this grounding for Miles and Gregor and the Vor system.

I started this post by mentioning that it was Bujold’s first Hugo-winning novel. People who don’t like Bujold talk about her fans as if they’re mindless hordes of zombies who vote her Hugos unthinkingly and because she’s Bujold. This is total bosh. When she writes something good, it gets nominated and often wins. The weaker books, even the weaker Miles books, don’t even get nominated. I think she’s won so many Hugos because she’s really good and because she’s doing things that not many people are doing, and doing them well, and thinking about what she’s doing—and because what she’s doing is something people like a lot. I think the system is working pretty well here.